nagoyasuzukiamerica.com – Millard Fillmore, the 13th President of the United States, holds a unique place in American history as the last president from the Whig Party. While often overshadowed by more prominent figures of his time, such as Abraham Lincoln, Franklin Pierce, and James Buchanan, Fillmore’s presidency is deeply intertwined with the political and social upheavals that preceded the Civil War. His time in office came at a critical juncture in American history, during the Antebellum period, when the nation was increasingly divided over issues like slavery, westward expansion, and state sovereignty.

Fillmore’s presidency was largely defined by his moderate political views, which, in many ways, mirrored the complexities of the age he inhabited. A former lawyer and politician from New York, Fillmore ascended to the presidency following the death of Zachary Taylor, the 12th President of the United States. Fillmore was chosen as the vice president to balance the ticket and bring political stability to the Whig Party. After Taylor’s unexpected death in 1850, Fillmore was thrust into the highest office in the land at a time when the country was on the brink of crisis. His actions during this period would prove crucial to the nation’s trajectory, for better or for worse.

This article will provide a comprehensive overview of Millard Fillmore’s presidency, examining his background, political philosophy, and the events that defined his time in office, including his role in the Compromise of 1850, his stance on slavery, and the decline of the Whig Party under his leadership.

The Rise of Millard Fillmore: A Background in Politics and Law

Early Life and Political Career

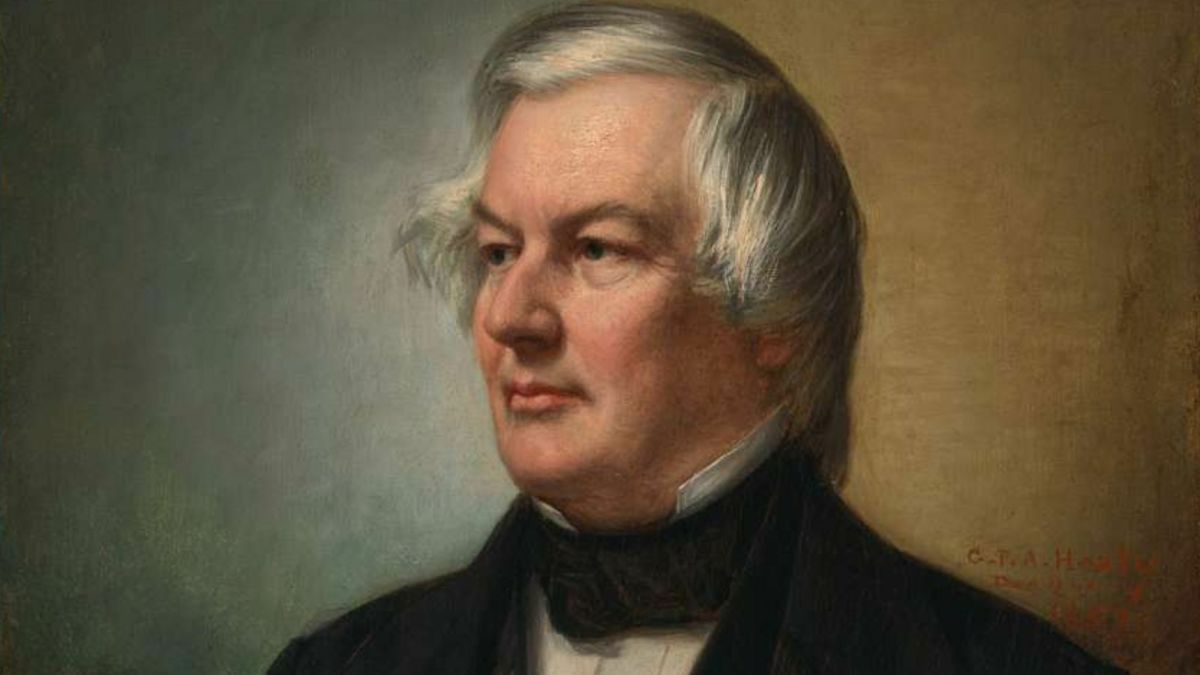

Born on January 7, 1800, in a log cabin in Cayuga County, New York, Millard Fillmore was the son of uneducated parents and grew up in relative poverty. Despite these challenges, Fillmore’s determination to succeed led him to pursue an education, eventually becoming a schoolteacher and later studying law. His legal career in Buffalo, New York, provided him with the political connections and recognition that would launch him into public life.

Fillmore’s early political career was marked by his affiliation with the Whig Party, a relatively new political organization that emerged in the 1830s as a response to the policies of President Andrew Jackson and the Democratic Party. The Whigs advocated for a more active role for the federal government in the economy, including internal improvements, a national bank, and protective tariffs. Fillmore aligned with these policies, and his early career saw him serve in the New York State Assembly and later in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Ascension to the Vice Presidency

Fillmore’s career continued to rise throughout the 1840s, and in 1848, he was selected as the running mate for Zachary Taylor, a war hero from the Mexican-American War, in the presidential election. Taylor was a political outsider with little experience in governance, so Fillmore, with his political acumen, was brought on as a stabilizing figure. When Taylor won the election and became president, Fillmore assumed the role of vice president.

However, in July 1850, President Taylor suddenly died from an illness, and Fillmore became the president of the United States. His ascension marked a turning point in the Whig Party and in the national debate over the growing divisions between North and South, particularly over the issue of slavery.

The Presidency of Millard Fillmore: Major Events and Political Challenges

The Compromise of 1850: A Landmark Moment in Fillmore’s Presidency

Fillmore’s presidency is perhaps most remembered for his role in passing the Compromise of 1850, a series of five separate bills designed to address the issue of slavery and territorial expansion in the United States. The Compromise of 1850 was crafted by some of the most prominent political figures of the time, including Senator Henry Clay and Senator Stephen A. Douglas, who hoped to bring peace to the divided nation.

The compromise included several key provisions:

- California was admitted as a free state, which upset the balance of free and slave states in the Union.

- The territories of New Mexico and Utah were created, and their status as free or slave states was to be decided by popular sovereignty, or the will of the people.

- The Fugitive Slave Act was passed, requiring that runaway slaves be returned to their owners, even if they had fled to free states.

- The slave trade was abolished in Washington, D.C., but slavery itself was still allowed to continue.

- Texas was compensated for relinquishing claims to certain territories in New Mexico.

Fillmore’s Support for the Compromise

While Fillmore did not come up with the plan himself, he threw his full support behind the Compromise of 1850. Recognizing that the nation was on the brink of disaster, Fillmore believed that the compromise was a necessary measure to avoid the disintegration of the Union. The country was deeply divided over the issue of slavery, and many Northern and Southern states were on the verge of secession.

Fillmore’s support for the Fugitive Slave Act, which required Northern states to return runaway slaves to their owners, was deeply controversial. Many in the North, especially abolitionists, saw the law as a severe infringement on human rights and an endorsement of the institution of slavery. While Fillmore was not a staunch supporter of slavery, he was willing to compromise in order to preserve the Union.

Though the Compromise of 1850 temporarily eased tensions, it was a highly divisive measure, and it ultimately failed to prevent the growing conflict between North and South over slavery. Despite its failure to resolve the issue in the long run, the compromise did buy the nation several more years of peace—years that allowed the North and South to further entrench their positions on the slavery question.

The Decline of the Whig Party

One of the significant consequences of Fillmore’s support for the Compromise of 1850 was the increasing fragmentation of the Whig Party. The party had long been a coalition of diverse factions, but the debate over slavery exposed deep rifts within the party. Northern Whigs, many of whom were opposed to the expansion of slavery, began to distance themselves from the Southern Whigs, who were more supportive of slavery.

Fillmore’s endorsement of the Fugitive Slave Act and the compromise alienated many Northern Whigs and abolitionists, and many Southern Whigs, in turn, began to see Fillmore as too moderate. The party, once the dominant political force, began to unravel, and by the mid-1850s, the Republican Party began to rise in prominence as the anti-slavery alternative.

Fillmore himself struggled to maintain the Whig coalition and faced increasing political isolation. He was unable to secure the Whig nomination for the 1852 presidential election, and the party soon collapsed. The American Party, also known as the Know-Nothing Party, which Fillmore joined after his presidency, never gained enough political traction to succeed the Whigs.

Fillmore’s Foreign Policy and Other Domestic Initiatives

In addition to the domestic challenges surrounding slavery and the Whig Party’s decline, Fillmore faced issues in foreign policy. His administration is often credited with opening diplomatic relations with Japan through the efforts of Commodore Matthew Perry, who sailed to Japan in 1853 to negotiate a trade treaty. The Treaty of Kanagawa was signed in 1854, marking the beginning of U.S.-Japan relations.

Domestically, Fillmore also continued to support internal improvements, such as the construction of railroads and infrastructure projects, in line with the Whig Party’s traditional focus on federal economic development. However, much of his domestic agenda was overshadowed by the more contentious issues of slavery and the Compromise of 1850.

The End of Fillmore’s Presidency and Political Career

After the White House

In 1852, Millard Fillmore was not selected as the Whig Party’s candidate for re-election. Franklin Pierce, the Democratic candidate, won the presidency that year. After leaving the White House, Fillmore’s political career was largely relegated to the sidelines.

In 1856, Fillmore made an attempt to return to national politics by running as the presidential candidate for the American Party, a nativist political group that largely opposed immigration and supported more conservative views on slavery. He was not successful, and the rise of the Republican Party, which opposed the expansion of slavery, effectively marked the end of Fillmore’s national political career.

Legacy

Millard Fillmore’s legacy is a mixed one. On one hand, he played a critical role in attempting to prevent a civil war during his presidency by supporting the Compromise of 1850 and keeping the Union intact, at least temporarily. On the other hand, his support for the Fugitive Slave Act and his failure to resolve the deeper issues of slavery and sectionalism left a bitter legacy, particularly in the North, where many viewed him as a figure who was too willing to compromise with the South.

Fillmore’s tenure represents the last breath of the Whig Party before its collapse and the rise of the Republican Party. His presidency stands as a reminder of the complexities of American politics in the years leading up to the Civil War and the difficult choices faced by leaders in times of national crisis.

Conclusion

Millard Fillmore’s presidency may have been short and overshadowed by the political and social crises that followed, but his role as the last Whig president and his support for the Compromise of 1850 ensured his place in history. While his attempts at moderation could not prevent the inevitable conflict over slavery, his actions during his time in office reflect the challenges faced by a divided nation and the precarious balance of power that existed in the years leading up to the Civil War. Fillmore may not be remembered as one of the great presidents of the United States, but his presidency remains a crucial chapter in the story of America’s journey toward civil war.